Juneteenth in Spacetime

When freedom and consciousness intersect.

Emancipation Day celebration, June 19, 1900

Juneteenth became a national holiday on Thursday. It’s Saturday, and we’re celebrating it. From vision to reality in 48 hours, like a candle bursting into flame.

I often say that the people who control this country – politically, economically, and in a myriad of other ways – are far too quick to offer symbolic rather than concrete justice, particularly when Democrats are in power. (Republicans often avoid offering any kind of justice, even the symbolic kind.) So, you might expect me to say that making Juneteenth a national holiday is nice and all but is no substitute for substantive reform. Not so. As we fight for substantive reform, we can recognize that it's a very important step forward.

I should preface anything I say by affirming the self-evident fact that the holiday is not about me or my ancestors. It is for Black Americans who are fighting still to overcome the legacy of freedom. But it’s also about the meaning of freedom, something all humans dream about.

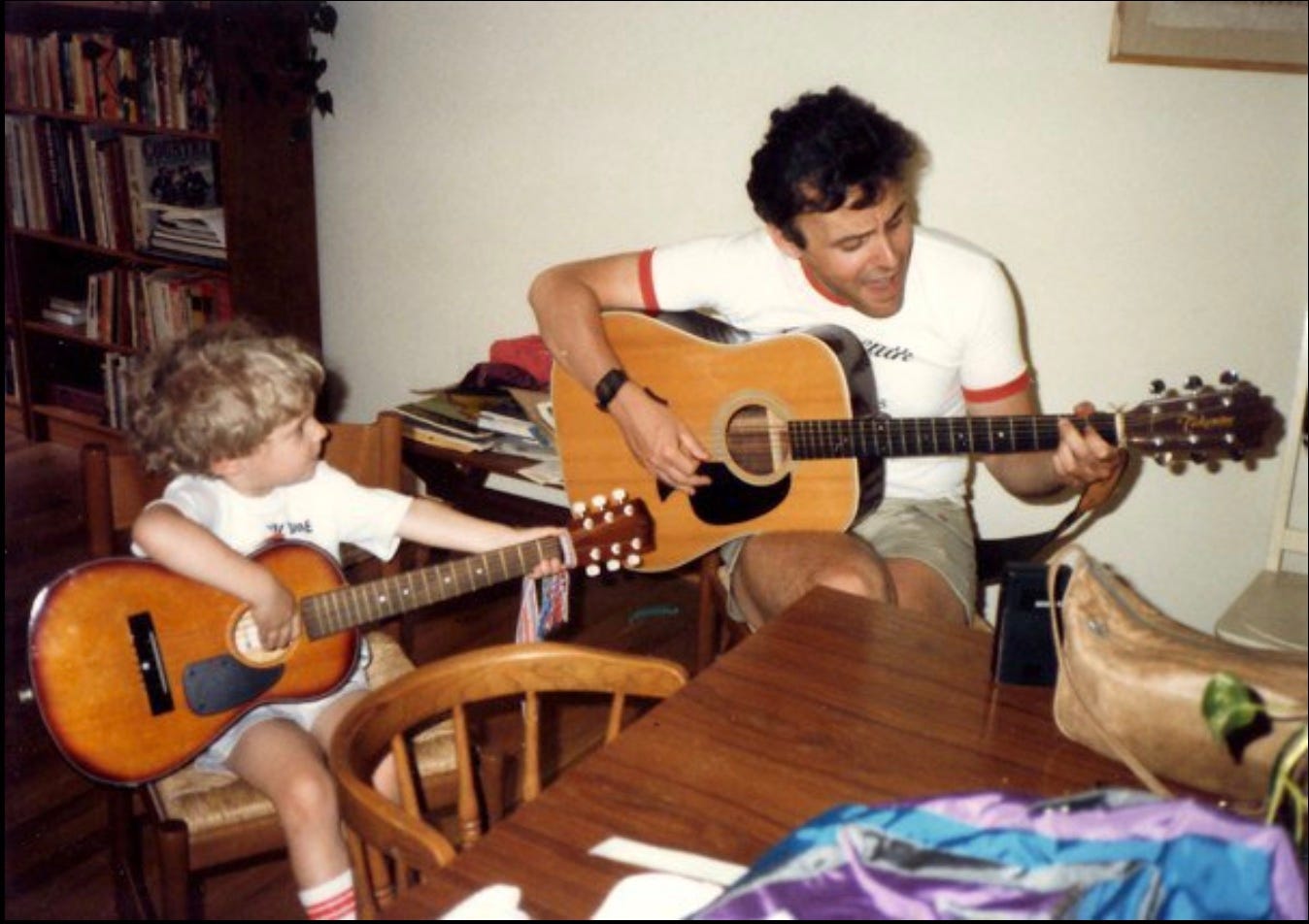

Now, about the shirt I’m wearing with my son in the (very old) picture above: I got this shirt roughly 40 years ago, at a time when very few people in the North, especially white people, knew what Juneteenth was. I certainly didn’t. I was a guitar player living in the East Bay and had a friend who did Afro-Caribbean music with kids. He was working with a group in the lower income section of Richmond, teaching the kids percussion, and they all decided they wanted to add electric guitar.

I came in and had to figure out what a guitar can do in an all-percussion ensemble. I treated it as a percussion instrument that could make notes, too, coming up with simple rhythmic figures, a little bit like montunos in Cuban music. There was a Juneteenth parade in Oakland that year, and the kids wanted to march in it. We rigged up a portable amplifier you could pull on a wagon, which somebody did while I walked beside connected by a cable and playing my little parts along with the kids.

It was a beautiful day, we all had fun and ate lots of great food, and at the end of it they gave me this t-shirt. The Black woman in the image seems to be the spirit of liberty and of life, symbolically rooted in the earth. Her fingers are outspread branches whose leaves are free Black men and women, dancing in the open air. I think the map at her feet represents the United States, with the black area representing the slave states, but I could easily be wrong. (If anyone knows, please let me know in the comments.)

The history books say that a Union general issued an order emancipating enslaved persons in Texas when he took command of troops garrisoned on Galveston Island on June 19, 1865. The story I was told was slightly different: that word got to the enslaved people of Texas by word of mouth on June 17, 18, and 19, hence the name “Juneteenth.”

Either way, I think of this holiday as a celebration of the power of knowledge. The enslaved people of Texas weren’t freed on June 19. The Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1862. The war itself had officially ended two months before. Like light from distant stars, freedom was carried along the curve of space and time, existent even when it was unknown. And, while General Gordon Granger issued his order on June 19, people only became physically emancipated as it was carried out by his soldiers.

But Juneteenth was a moment of liberatory knowledge, a point in spacetime where freedom and awareness intersected. That matters, because freedom is a state of mind as well as a physical state. That, to me, is the beauty of Juneteenth. It’s won through a combination of physical struggle and the light of consciousness. It is a holiday for Black Americans, not for me. But it also reminds white America of its obligation to make full restitution and reparation for the harm that was done and the harm that continues to be done. And it is a message to all of us that our collective freedom is won through the when body, mind, and spirit work in harmony for the betterment of all.

Juneteenth is a time for the descendants of the enslaved to celebrate, for the beneficiaries of slavery to reflect, and for all of us to meet on the higher ground that awaits us outside space and time.